P>It was cracking everybody. Mitch, poor Jason, your moto. I didn't want to make this video in my effect. I made this video a few months ago when I found out the bad news, but I ended up deleting it. I said, "You know, I'm not gonna fucking upload it." But now, I just say, "Fuck you, man. Fuck you, man." Your bonus, right in your bones. You wanna, they're gonna give you a bonus. Your recruiter doesn't matter who you are, Air Force, Navy, Marines, Army. I was offered a $3,500 bonus back in 2003, and in 2009, I realistically got $5,000. Yeah, and they're gonna recoup that. If you don't know what the word recoupment means, they're gonna take all that money back, all that money that I earned, all because of some bullshit policies. When I first came in the Army, you're a civilian. You don't know shit, you don't know nothing. Right, they tell you, "Where to sign on the dotted lines, you sign it. You just sign here, sign here, sign here, sign here. Bam, bam, bam. You do everything they tell you because you want in so bad." Apparently, what I didn't know was that when you do an enlistment bonus, any kind of bonus, it's supposed to be on the same date as your enlistment contract. So, let's say, for hypothetical reasons, on March 10th is your enlistment day, your bonus better be signed on that exact date. It can't be a day before, it can't be a day after. All the dates have to be the same date or they're gonna fucking hit you with a recoupment. So, if you're a current military or you're about to join the military, you need to go look back and look for that shit right...

Award-winning PDF software

Army not getting paid Form: What You Should Know

G.

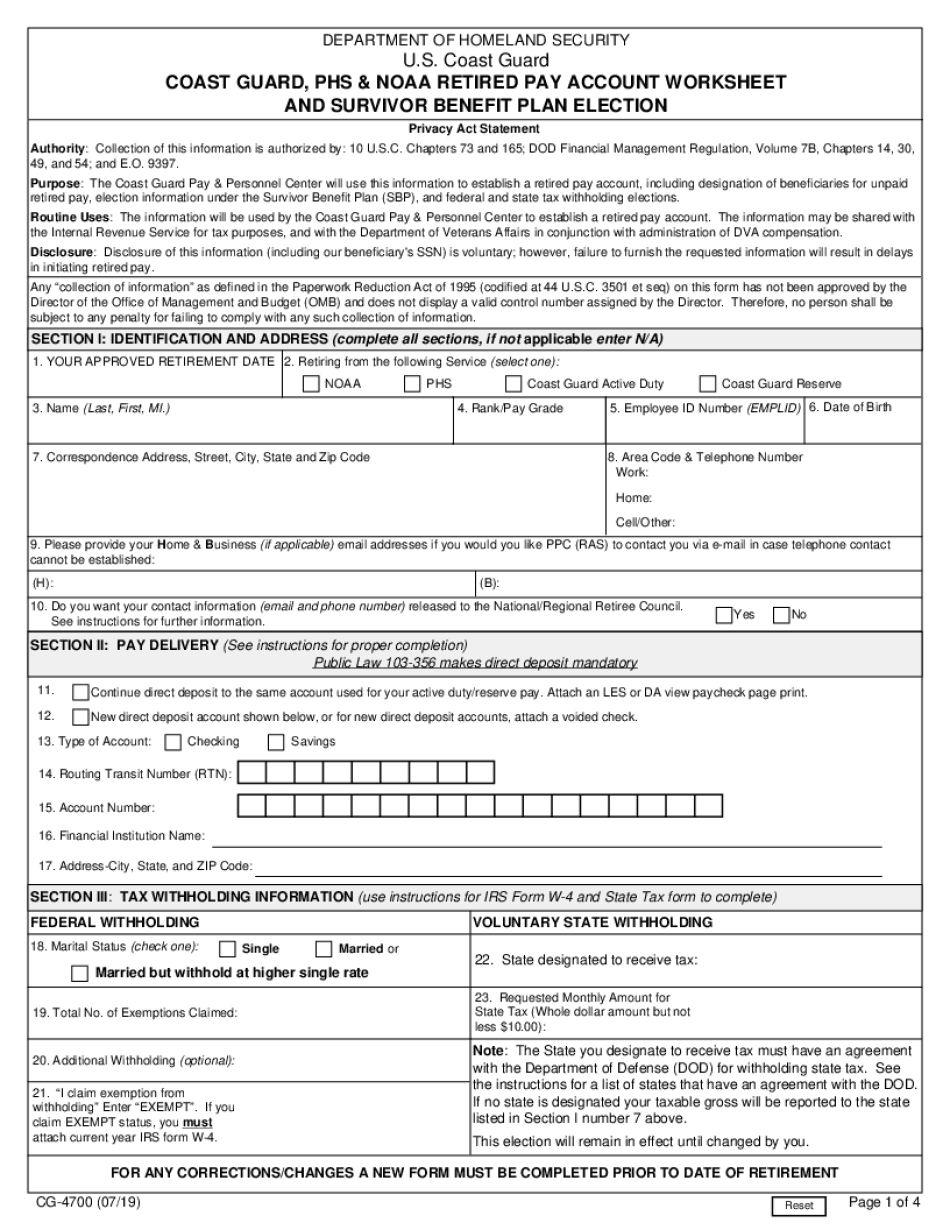

online solutions help you to manage your record administration along with raise the efficiency of the workflows. Stick to the fast guide to do USCG CG-4700, steer clear of blunders along with furnish it in a timely manner:

How to complete any USCG CG-4700 online: - On the site with all the document, click on Begin immediately along with complete for the editor.

- Use your indications to submit established track record areas.

- Add your own info and speak to data.

- Make sure that you enter correct details and numbers throughout suitable areas.

- Very carefully confirm the content of the form as well as grammar along with punctuational.

- Navigate to Support area when you have questions or perhaps handle our assistance team.

- Place an electronic digital unique in your USCG CG-4700 by using Sign Device.

- After the form is fully gone, media Completed.

- Deliver the particular prepared document by way of electronic mail or facsimile, art print it out or perhaps reduce the gadget.

PDF editor permits you to help make changes to your USCG CG-4700 from the internet connected gadget, personalize it based on your requirements, indicator this in electronic format and also disperse differently.

Video instructions and help with filling out and completing Army not getting paid